The period of Ottoman rule over the Balkans is still triggering even today for Christians across the Balkans. Much of their current lives were crafted by four centuries of Ottoman rule. A particularly vivid piece of national memory throughout the Balkans is the devşirme system. The devşirme system sustained the famed janissary corps, elite Ottoman infantry soldiers who were taken from Christian subjects as boys. The opportunities for advancement and the agony of losing one’s child were intertwined with the devşirme system. But when the devşirme system was abolished during the 17th century, the janissaries, who continued after the discontinuation of the system, lost the attributes that made them the powerful warrior force of previous centuries.

The Devşirme System

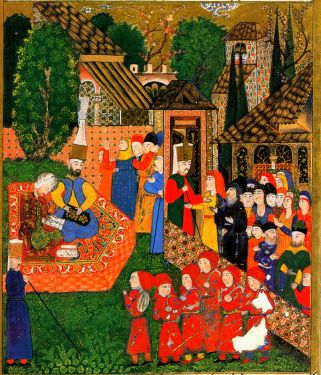

The devşirme system was a forced levy of the most promising Christian boys in the Balkans. Every three to seven years, Ottoman troops traveled to Christian villages and levied this human tax, often referred to as a blood tax by Christians. The brightest and most attractive boys, between ages 8 and 18, would be taken and run through quick training to assess their abilities. Those that did not make the cut went to serve in the households of Ottoman provincial nobles, the sipahis, before eventually going to Istanbul to serve in other duties.

The best of the best would be taken back to the Ottoman capital of Istanbul and raised in palace schools, where they received a superb education and military training. They were forced to convert to Islam, although forced conversions actually go against Sharia law, but since, like in most historic Muslim states, non-Muslims could not bear arms, this was a necessary step and also dissolved their old religious loyalties. By having the boys learn Turkish, the Ottoman authorities also ground away at their ethnic loyalties. Through their education they were also instilled with a sense of supreme loyalty to the Ottoman state by removing their previous ethnic or religious affiliation and replacing it with a dedication to the Ottoman Empire and its sultan.

Based on their intelligence and latent capabilities, the boys would be set down a path for the bureaucracy or the janissary corps. From this privileged positions they could become Ottoman scribes, guards, governors, or even grand viziers, among other prestigious posts. But while they could gain immense prestige and power, the boys taken by the devşirme were still effectively slaves of the state. The majority of these elite would serve in the janissary corps.

The Janissaries

The janissaries, or yeni çeri (new troops), were the elite military unit of the Ottoman sultans. This was an ideal crack force of troops for the sultan, given that the soldiers effectively had no families, received excellent military training, and were dedicated to him; in short, the perfect standing slave army. They were initially not allowed to marry until after retirement, allowing their only sense of familial loyalty to be to the state and their fellow janissaries. They were also paid wages, unlike most armies of the time, which helped to ensure their absolute loyalty.

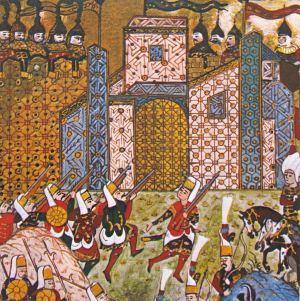

The janissaries were originally trained in archery and with hand-to-hand combat weapons, but firearms were quickly introduced into their repertoire. Given the extreme inaccuracy and difficulty of use of early firearms such as the musket and arquebus, only a permanent, trained army could effectively use them. Since the janissaries were a standing army, they were the perfect fit. The Ottoman army was initially the most effective user of gunpowder weapons, decades ahead of their Christian contemporaries in Europe. Their mastery of cannon contributed to their eventual 1453 conquest of the city of Constantinople, whose physical defenses were some of the most formidable of the medieval period.

To Encourage or Resist

Some parents would purposefully try to sacrifice their children to the devşirme system. Life in the Balkans was hard, and by sacrificing their sons, parents were potentially offering them a better future than they could have following the family trade. It could also be the family’s chance at securing its own future. If their lost son became a janissary or minister and remembered his old family, he could potentially assist them. In addition, a larger family possibly couldn’t sustain all of its children due to a lack of resources or poor harvests; sacrificing one to the devşirme allowed the others to have a better chance of survival in a harsh world. There are some cases where families even bribed the Ottoman collectors to take their sons.

But other families would actively resist giving their sons up. To them, their children’s freedom and religion were more important than any potential gains the family or the boys could garner through their abduction. Some children were hidden when Ottoman collectors approached the village. Some were even mutilated by their parents to prevent them from being taken. The Ottomans only wanted the most perfect children as recruits for the devşirme system, so ones with obvious disfigurement were not taken. The most common method would be to cut off the boy’s pinky finger, as this would be the least harmful to their ability to work while still rendering them unfit for the devşirme.

Despite their contributions to the Ottoman sultans, the abductions of the devşirme were undoubtedly harmful to the development of the Christian peoples of the Balkans. By taking the best and brightest of Balkan children for several generations, the Ottomans undermined the progress of these communities.

A History of the Devşirme System

The devşirme system had begun at the end of the 14th century under Murat I (r. 1362-1389). During the middle of the 14th century, the Ottomans had expanded their budding empire into Europe and started to rule over an increasingly large Christian population. While the first janissaries were most likely prisoners of war, the devsirme was quickly introduced both as a way to keep the Ottomans’ Christian subjects in line and to draw on a ready supply of troops that couldn’t normally be accessed (since non-Muslims couldn’t bear armies in the first centuries of the Ottoman Empire). Under the first Ottoman sultans, the janissaries were the elite force that turned the tides of battle, or pushed the victory home, in fields of combat from Hungary to the gates of Persia.

The initial janissary corps was rather small (most likely only a few thousand men at maximum) and their status as slaves was tightly controlled. But by the fifteenth century, the janissaries started to be granted increased privileges. By the next century they could marry while still in military service, and their sons could also enter the janissary corps. This directly led to two major problems: 1) the janissaries now had families of their own that were the crux of their loyalty, undermining their absolute loyalty to the state; and 2) the janissary corps grew exponentially larger, becoming increasingly unwieldy for the Ottoman sultans.

Soon the janissaries were a state inside a state. Their first revolt was in 1449, demanding higher wages, but they became increasingly frequent and violent from the seventeenth century. A janissary revolt killed Sultan Osman II (r. 1618-1622) in 1622 and Sultan Ibrahim (r. 1640-1648) was overthrown and killed in 1648.

The devşirme system had been unpopular among the Muslim population of the Ottoman Empire as well as the Christian, since only those born as Christians could become part of the janissaries. In 1683, Mahmud IV (r. 1648-1687) abolished the devşirme, and the janissary corps were then open to all Christian and Muslim free men.

The Janissaries Continue

Since being a janissary was a paid position, a number of abuses rose up now that the janissary corps was not composed of slaves. By this time the janissaries numbered over 100,000 members, compared to only a few thousand a century and a half before. Long-dead soldiers were kept on the books by the janissaries so they would get more money from the state; martial discipline practically disappeared as the old training system fell apart in the face of thousands of Ottomans applying for service as janissaries, but many practiced their own trades and merely took the income from their janissary pay.

In previous generations, even if they had become more restive by the mid-15th century, the janissaries were at least incomparable warriors. Now they were merely a burden on the state. As Christian Europe started to outstrip the Ottoman Empire technologically by the mid-17th century, Ottoman armies were forced on the defensive. The once vaunted janissaries lost battle after battle against the armies of the Habsburgs, Poland, and Russia during the 17th and 18th centuries.

And meanwhile they were getting larger and larger, eating up an increasing large part of the Ottoman budget, and rebelling on regular intervals. Instead of protecting the Ottoman sultan, they were proving to be his greatest threat. In addition to Osman II and Ibrahim, at least four other sultans went down due to janissary revolts (16.67% of all Ottoman sultans). Selim III (r. 1789-1807) tried to create a Western-style army, the Nizam-ı Cedid (“New Order”), with which to replace the janissaries, but he was deposed by the janissaries first. The janissaries effectively had mastery over the Ottoman Empire and were using it for their own gain with little regard to who sat on the throne or how the state was doing, as long as their position and income were assured.

It was Selim’s cousin, Mahmud II (r. 1808-1839), who would finally take the janissaries out. By this time there were 135,000 janissaries draining the Ottoman coffers and threatening the sultan’s authority. Mahmud moved slowly, but in 1826 he launched his plan: rumors of another Western-style army were leaked and the janissaries revolted, but Mahmud, away from the capital, invoked the support of his prepared loyal forces, as well as the Ottoman people, to resist the janissaries. The common people, who hated the janissaries for their arrogance and privilege, gladly complied. Forces loyal to Mahmud defeated the janissaries. On June 15, 1826, the “Auspicious Incident” took place, and Mahmud forced the disbandment of the janissary corps, ending their nearly 500 year history.

Conclusion

In the early centuries of the Ottoman Empire, the janissaries, bred by the devşirme system, had been a superb body of troops that greatly contributed to continued Ottoman expansion; the image of the “Terrible Turk” struck fear into the heart of Christian Europe. Regardless of the ethical and human rights problems posed by the devşirme system, at least it did its intended purpose. But when the janissary system changed, it lost all of the hallmarks that made the janissaries such a superb unit. In the end, the janissaries had become the deadliest threat to the Ottoman sultan, and it is a great irony of history that a corps that had done so much to expand the Ottoman Empire had to be put down to save that same empire.

June 25, 2018 at 8:56 am

You make it seem parents willingly gave away their children. This is despicable lie. It was enslavement. Also the janissary were not elite troops they were cannon fodder or whatever the expression was at the time. The empire relied on sending poorly trained soldiers of non muslim origins in the front lines to exhaust the enemy’s fire power. Yes if a janissary were to miraculously survive enough fights they would be promoted. Also their training consisted of torture to force them to accept islam and some were raped by the muslims on the back door. That is because the muslims do not and did not consider anything a crime if it is against a khafir i.e. a non-believer. They were skilled because those that were not died pretty fast in the first 1-3 skirmishes. Although many things are factual it seems to me you are trying to wash away the many crimes of the Otoman empire.

LikeLike

June 30, 2018 at 11:47 am

No, I certainly do not mean to whitewash Ottoman history. For most parents, it would have been a terrible loss and as I mention in the blog, some parents even took drastic steps such as disfiguring their own sons to prevent them from being taken in the devshirme. Indeed, there were crimes carried out against the taken boys, including forcible conversion and rape as you mentioned. But there are documented cases where parents tried to have their sons taken by the devshirme in order to give them a better life. Jelavich succinctly made the point in “The Balkans:” “at home his opportunities were pitifully limited; in Constantinople he could rise to administer the empire.” You can see the works of Charles and Barbara Jelavich (Balkan historians), Caroline Finkel (Ottoman historian), David Brewer (Greek historian), and others supporting this. Furthermore, your characterization of Islam is very overreaching – the Koran and hadiths have several injunctions regarding proper behavior toward non-Muslims, and especially toward fellow People of the Book (Christians and Jews), which of course includes the Balkan Christians that were taken in the devshirme. Finally, while the janissaries certainly declined in actual martial prowess, they were never considered mere cannon fodder. The “cannon fodder” troops were usually the Azabs, irregular Muslim peasant infantry, and especially those known as the basibozuks (“crazy-heads”). Far too much was spent on training the janissaries to just throw them away. Certainly janissaries died in battle, as was the case with all military forces, whether cannon fodder or elite guards. The janissaries were, at least while composed of devshirme conscripts, an elite force.

LikeLike